Loyalty Coalitions are Morphing into Marketplaces

“I am not happy with it [the 15% commission rate], but you do get a constant stream of millions of users…”

This quote comes from a 2015 Guardian article on Amazon, but the sentiment could apply to almost any business that ever paid a fee to participate in a marketplace.

This challenge – the give-and-take of marketplaces – now firmly belongs on the agenda of loyalty strategy meetings.

This blog serves two purposes.

First, it gives marketers a basic grounding in economics which can directly impact on your loyalty strategy, complete with real-world examples of brands putting the theory into practice.

Second, if you’re already familiar with the economics, it provides a narrative framework for upskilling your own teams, to help everyone you work with understand what will drive success and failure in loyalty marketing.

For all readers, the key takeaway will be that loyalty programs should embrace characteristics of marketplaces in order to maximize appeal to your target customers.

We are not suggesting that coalitions should become marketplaces like Amazon, Expedia, or Alibaba; rather, that having your brand co-exist in broader ecosystems will increase visibility and relevance that engages with mid-tail and longer-tail customers.

This is a good thing.

Marketplaces deliver unique value for customers that your own brand cannot deliver on its own.

Time to grab a slice of the pie.

A successful market depends on shared space

A guy in a field with a cow for sale does not a cattle market make.

Equally, two guys in two different fields with two cows is still not a market.

In a marketplace, multiple traders appear in one place so the customer can:

- compare offerings (i.e., see both cows in one field)

- rely on the market to select trustworthy suppliers

- benefit from value-added services (such as free delivery, content aggregation, etc.).

The souk, the shopping mall, Online Travel Agencies, and Amazon.com are all testament to this reality.

Unfortunately, many loyalty programs still resemble different guys in disparate fields with different cows.

This creates a terrible customer experience.

As I recently explained, when each individual brand operates a separate loyalty program, it pulls the customer in countless different directions – and dilutes the benefits for every participating brand.

So loyalty programs are, over time, naturally morphing into shared spaces.

The most commonly successful model is a loyalty program built around a strong brand at the centre.

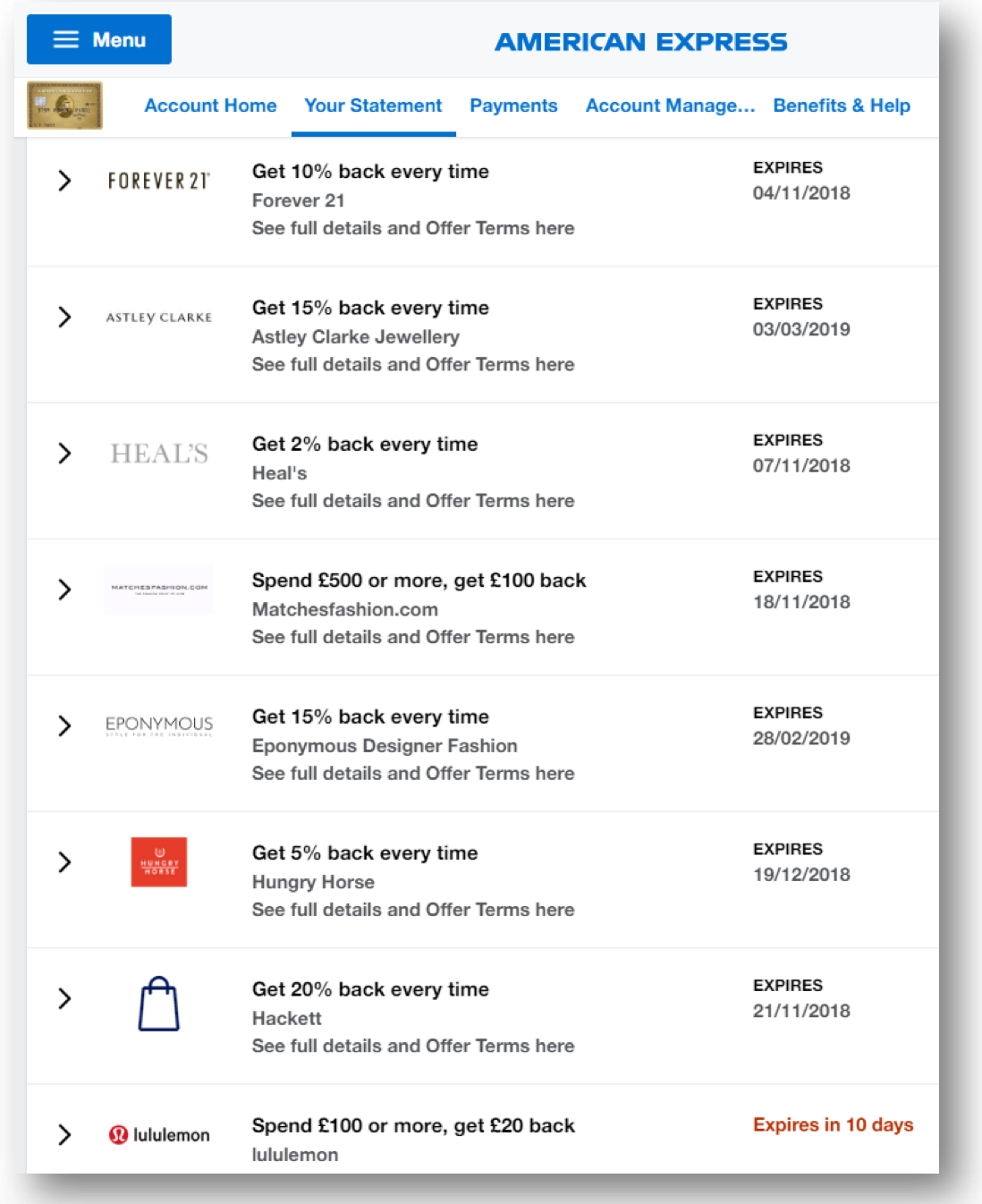

The Amex “Offers” space is a good example.

It creates unique value for customers, by allowing them to redeem offers and spend reward points with many different brands.

There are variations on the same theme.

For nearly 30 years, Hertz and Avis have permitted customers to earn points in the currencies of many different loyalty programs.

Hilton requires customers to earn in their proprietary program, but enables exchange to complementary programs.

Other examples include Tesco Clubcard, Miles & More, Marriott Rewards – all shared spaces for individual customers to shop many different businesses.

This shared space creates investable value for businesses – which explains why Amazon Marketplace is able to charge a 15% tax on participation.

Indeed, some loyalty program operators have got greedy.

Nectar Points, Air Miles and Amex’s short-lived Plenti all ran into trouble at least in part because their high fees prevented brands from passing sufficient value on to consumers.

But when the shared space works, while the dynamics primarily benefit the lead brand, the value-added customer experience of the marketplace helps every participating business grow.

Successful markets, and successful loyalty programs, increasingly depend on shared space.

Markets work better at scale

As merchants co-locate, they begin to enjoy economies of scale.

Illustratively: when I was growing up in the 1970s, car dealerships were on opposite sides of town.

Today, however, car dealers are grouped into an “auto row”, whereby dealers “share advertising costs” and “attract ancillary businesses including car washes, insurance offices, and body shops that benefit all of the dealerships”[1].

The same logic applies to loyalty brands.

Consider the travel sector.

For hundreds of years, travel brokers (now evolved into online travel agencies) have provided useful online real-estate and advertising services, which brands would otherwise have to fund and maintain on their own.

Demand also becomes aggregated at scale.

With low-frequency, high-value sales such as cars or vacations, customers may show less brand loyalty, and so they come to the shared marketplace to make an informed comparison.

Participating in that shared space ensures you get noticed when the customer decides to buy, and you grow a more efficient business as a result.

Hotel loyalty programs are coming round to this view.

They are mostly geared towards business travellers; but as hospitality expert Douglas Rice discussed last month, 75 – 80% of hotel guests are infrequent holidaymakers.

This is a missed revenue opportunity.

So during the past 10 years, brand-led loyalty coalitions such as Hilton Honors have allowed less-frequent customers to earn their currency in everyday retail locations such as fuel, fashion and food outlets.

The customer may not be shopping for a vacation every week, but the retail partner keeps Hilton (and its loyalty program) front of mind.

This scale works equally well for brands on both sides of the “earn and burn” game.

While the higher-margin travel brand, or “burn partner” gains everyday opportunities for earning which it cannot provide on its own, the lower-margin, higher-frequency retailer or “earn partner” becomes able to incentivize loyalty by offering desirable rewards, such as the aspirational flight or hotel.

Ideally, all brands get meaningful and actionable data on a far wider audience, and enjoy a better marketing ROI as well as a net uplift in sales.

Successful markets, and successful loyalty programs, work far better at scale.

Liquidity facilitates growth of loyalty markets

You don t normally hear marketing people talk about “marketplace liquidity,” so it needs explaining.

Consider the origin of money.

Thousands of years ago, marketplaces led to coins being minted so that people would not have to carry around three sheep or five sacks of potatoes with which to trade.

This made markets more successful. Trade became easier and less expensive, and merchants could bring consumers more choice, and at lower cost.

So liquidity is generally a good thing in marketplaces – and when you work in financial services, you tend to invest heavily in improving it.

In loyalty marketing, you make those improvements by treating points more like money: simplified rules for earning and redeeming, more places to spend, more choice for the customer.

But early loyalty programs suffered from very little liquidity.

They were designed to be standalone, so the vast majority of people ended up collecting a tiny number of points across dozens of programs, with little expectation of ever accumulating enough value in any one program to redeem for something they really wanted.

Such fragmentation is why many customers either quit the programs, or never join in the first place.

Brands are now tackling this problem.

The major changes started in 2017 with Hilton allowing members to use their points at Amazon, as well as Choice Hotels[2] and La Quinta enabling members much more freedom in using their points value.

Wyndham, too, has dramatically simplified its program – making it easier for customers to engage and benefit. Emirates, Etihad, and United Airlines joined the party, adding many more partners.

These efforts were rewarded with significant growth in membership, but more importantly, a significant growth in activity among the base of existing loyalty program members.

All that said, total liquidity (or freedom) would be counter-productive, and so the entities which govern marketplaces seek to restrict it.

To return to money, governments control liquidity to prevent crime.

Illustratively, scrap metal traders in the UK are now banned from accepting cash in order to create a less liquid market for stolen copper[3].

Similarly, brands would much rather you did not spend their points literally anywhere.

If you could earn points at Sainsbury’s and redeem them at Tesco, that would defeat the purpose of the loyalty program in the first place.

So as loyalty coalitions morph into marketplaces, loyalty currencies must become more liquid; equally, brands must adjust that liquidity over time to protect their interests.

Liquidity – appropriately delimited – drives growth in marketplaces.

Loyalty coalitions are no exception.

Loyalty coalitions need competition to stay healthy

Imagine the last time you went into a European-style marketplace.

There were dozens of vendors of basically the same products; however, each vendor survives and has a loyal clientele.

Why?

The answer is that a healthy market actually benefits from competition.

In the 19th century, the market for canned goods was uncompetitive – and decidedly unhealthy.

“The people are in constant danger of buying unwholesome canned meat; the dealers are unscrupulous…”[viii]

This might have put people off buying canned goods at all, which would have been bad for every supplier in the market.

But as production costs fell, the market became crowded and suppliers upped their game.

Indeed, the first ever brand – the William Underwood Company’s devil logo – was trademarked in 1867 as a direct answer to the perils of unreliable packaged foods.

Customers now expect to make purchasing decisions based on the three primary battlegrounds for differentiation:

- service/convenience

- price

- brand

…and the customer trusts market forces to push up standards on all fronts.

To return to loyalty: the American Express marketplace introduced previously features four fashion retailers:

- Eponymous

- Fashion 21

- Lululemon

- Hackett.

There is some crossover between these brands, and by participating in the same market, each inevitably sacrifices some trade to the others.

But there are also differentiators.

Forever 21 and Eponymous cater for different budgets, Hackett is a men’s specialist, and Lululemon designs and sells women’s sportswear.

No single brand can outcompete the others in all categories; equally, different customers will have different reasons for perceiving each brand as special.

This competition creates more choice for customers, and draws more business for each competing brand, with some using marketing strategies such as seo saas to reach them.

This is the foundation of what we refer to as Loyalty Coalition V2.0: where a strong central brand takes responsibility for organizing the stakeholders in their ecosystem and the balance of competition and differentiation between them.

Under the decentralized, V3.0 coalition model, the responsibility for managing this balance will pass from a single central entity to all of the participating brands – effectively leading to the marketplace becoming governed by market forces of its own.

The key point in V3.0 coalitions is that all brands co-exist and collaborate as peers, each serving customers with a differentiated loyalty proposition.

Building your own loyalty marketplace is easier than you might think; visit Currency Alliance to find out more.

Markets evolve, and so must their participants

Markets – whatever kind – inevitably also become markets for ideas.

Participants are continually challenged to update their businesses to cope with marketplace demands, creating a constant requirement for innovation.

In consumer goods, these demands have manifested as a constant downward pressure on margins, creating an experience economy where brands must offer something extra to earn loyalty and survive.

This is what gave rise to the “earn and burn” system: where “burn” partners offer the something extra, whilst the “earn” brand shares in the loyalty that those experiences engender.

So brands on both sides of the earn-and-burn game need each other now more than ever.

Technology has held them back: slow, limited, expensive technologies – dependent on hardcoded integrations and dominated by self-interested third parties – may be keeping you from forging collaborations that best serve your customers’ needs.

But technology has a habit of catching up with markets, and eventually driving change.

In 2017, some loyalty software vendors began migrating to some variant of the SaaS model.

The largest vendors are really only using this “SaaS” term to indicate that their software is cloud-based – but more evolved iterations also bring the benefits of:

- lightweight API integration

- easy interaction between your existing CRM and campaign management systems

- pay-as-you-go service with no upfront fees

- marcomms integrations across more consumer touchpoints.

This will happen because the laws of markets are at play.

Booming global trade led to the design of bigger, faster, safer ships.

Growing populations drove taller, sturdier buildings in which people could live and work.

Internet usage has grown so fast that websites from five years ago now often appear very outdated.

The same is happening in loyalty marketing.

Often, innovation was constrained by lack of significant new budget; but spiralling digital interactions between customers and brands are driving a booming trade in marketing technologies – many of which are so efficient and effective, they actually help reduce other marketing costs.

With the barriers to change now greatly reduced, and the right tools at their fingertips, there is no reason marketers cannot make their own brand a leading agent of change in its own loyalty marketplace.

Build your own loyalty marketplace with Currency Alliance

By looking at the current loyalty industry trajectory in light of the wider history of marketplaces, it’s clear we’re heading towards the emergence of loyalty marketplaces with the following characteristics:

- Shared spaces: in which complementary brands, on both the “earn” and “burn” sides, co-exist and operate transparently, with no one party dictating compliance requirements

- Scale: brands pooling resources for efficiency, aggregating demand across international borders, and creating appealing choice for the greatest possible number of customers

- Liquidity: brands treating loyalty currencies more like money, creating more freedom for customers – but with the necessary controls to protect ROI

- Competition: well-curated symbiosis between brands with overlapping offerings, to attract a wider market of customers who demand easy access to a wide range of choice

- Evolution: enabled by inexpensive, agile, decentralised software, designed to change and adapt in response to shifting marketplace conditions.

Despite the pace of change, full manifestation of loyalty marketplaces will take some time.

While major loyalty programs all show the green shoots of change, there is not one major loyalty brand which is not, in some way at least, being held back by the simple realities of being part of a major corporation: office politics, inherent strategic conservatism, embedded business processes, and – not least of all – cumbersome legacy technology systems.

The last of these is easily resolved.

The Currency Alliance SaaS platform was built to allow brands to forge the coalitions that make sense for their businesses – exercising complete control over their chosen partners to ensure the greatest relevancy for their customers.

Currency Alliance charges no CapEx, license fees, monthly minimums, or maintenance costs: none of the financial obstacles that have historically constrained loyalty program ROI. Partners pay just 2% of the value of loyalty points transacted on the platform.

And with seamless API integration, it co-exists with your existing CRM and campaign management systems so you don t end up with customer data in additional silos.

Visit Currency Alliance.com to find out more.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auto_row

[2] https://esellercafe.com/hilton-honors-members-can-now-use-points-shop-amazon/

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-20568327