How to win C-suite buy-in for loyalty marketing

You’d hope that the C-suite would be enthusiastic to fund growth in the loyalty program, because effective loyalty marketing represents huge upside potential, when the program aligns with company objectives and shared values with customers. In the case of the most popular programs, they also represent a major share of companies’ current enterprise value.

Yet historically, winning backing from the C-suite for loyalty initiatives has been difficult. Loyalty best-practices are little understood by people outside of the profession, and the program itself is often seen as a cost-center by senior leadership team.

As a result, many enterprise programs are throttled by underinvestment. So the purpose of this article is to set out how to address this challenge, and help your loyalty team secure the resources needed to influence customer preference for your brand.

In the first section, we’ll discuss the common challenges that loyalty programs face in proving ROI and how to work around those challenges.

Then in the following three sections, we’ll discuss three common areas of misalignment around loyalty best-practices, and suggest how to prove that these concepts are key to unleashing your program’s revenue-generating potential.

These concepts are as follows:

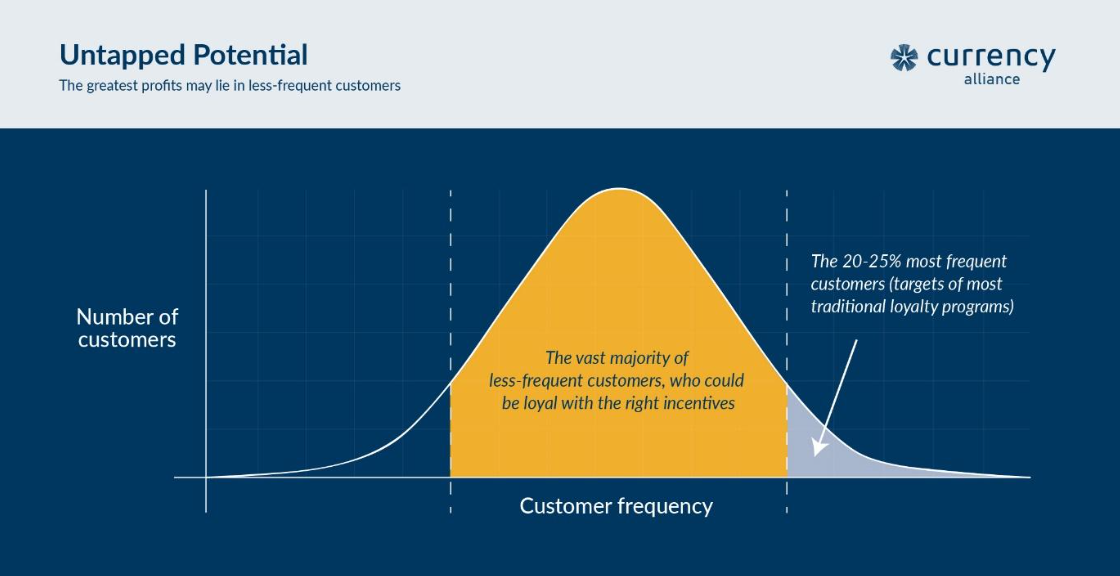

- your biggest growth segment is in the less-frequent customer. High-spending customers should certainly be rewarded, but too many rewards are often showered on customers who’d shop your brand frequently anyway. Greater upside lies in the customers who aren’t loyal yet – but who have the potential to be, with the right incentives

- it’s the loyalty team’s job to accelerate earning and customer frequency. Some business leaders may regard high levels of points issuance and redemptions as ‘expensive’. This is upside-down thinking. Higher frequency should equate to greater ROI from cash transactions, from the sale of points to partners, and from the collection of zero-party customer data which supercharges marketing personalization across your business

- the types of partnerships needed. CEOs may be happy about signing 2-4 partnerships a year with airlines, banks, hotels, etc. But smaller partners across the spectrum of your customers’ everyday spending, in retail, quick-service restaurants, entertainment, mobility, etc. are needed to engage the less-frequent customer, and allow them to earn and burn more frequently. This spins the flywheel of accelerated customer engagement, that increases loyalty ROI by improving Customer Lifetime Value (CLV).

The people who hold the purse strings for new loyalty investment are probably not loyalty experts. Even if they are loyalty experts: CEOs often fail to notice brilliant ideas because they’re simply too busy to pay attention.

So, you need to anticipate responding to these scenarios quickly: where the CEO or CFO demands cost-cutting in your loyalty program, or where your budget is up for review and you’re pushing for growth. Money can certainly be wasted in any area of the business, but wisely invested, there are few better alternatives than loyalty marketing for investing in customers to maintain a healthy business.

If you’re not already in the habit of collecting and reporting the necessary KPIs to senior management, it might take months or longer to capture the necessary insight, and educate stakeholders on what that insight implies.

So even if you’re not currently negotiating budgets or setting company priorities, your everyday role needs to expand beyond simply running the loyalty program, to proving its growth potential and positioning it to help the business grow.

The challenge of proving the value of customer loyalty

It’s widely known that a loyalty program directly and indirectly supports a significant share of a company’s enterprise value. But many members of the C-suite may not understand where this value comes from.

They might, for instance, believe it’s simply because the loyalty program is an extension of a popular brand – rather than believing that the loyalty program is part of the reason the business is successful. The connection between loyalty investment and high customer frequency, and larger basket sizes, may not be clear to all stakeholders.

So, while loyalty practitioners might see further investment in their programs as an obvious way to influence growth, that message might be lost on the C-suite. Similarly: the loyalty team may be alarmed at points devaluations, but the C-suite might see them as an easy way to cut costs or prop-up the balance sheet, not foreseeing any negative impact on the fortunes of the wider business.

So, you need to show ROI on loyalty investment, while planning and communicating loyalty program changes carefully.

In 2022, Forrester proposed a very comprehensive model for calculating loyalty ROI – which you should work through as a loyalty team – but it will be too involved for the C-suite.

However, going through these measurement exercises will help distil what 2-3 key messages or indicators may most resonate with leadership.

Historically, showing ROI on the overall program has been difficult for most loyalty teams, in part due to poor linkage between loyalty initiatives, technology system, operations costs, and the impact on commercial results. Back in 2019, I participated in a study by The Wise Marketer into why loyalty programs underperform, alongside 33 other industry specialists. The top 4 reasons given were:

- Poor use of data

- Difficulty proving program performance

- Inadequate communications and dialog (customer-side)

- Inadequate C-level support.

The industry has made strides since this report was published, but in 2019, ‘inadequate C-level support’ was cited by 83% of panellists and I doubt the figure would be much lower today. Of course, proving performance with data is how you muster C-level support – so three of these challenges are part of the same problem.

Focusing on what you can prove

What should be easier is to talk about ROI at customer-level, i.e., say that +/- 20% in points value will have a predictable impact on the customer spending more cash with your brand, or quitting the program.

This predicted impact of change is important, because it can guide the conversation beyond generic statements about the importance of customer loyalty. To cite one widely circulated, but unhelpful statistic…

‘The average loyalty program member spends 25-40% more than non-members’

As Adam Posner points, this is probably the result of self-selection; people who are going to spend more are more likely to join the program in the first place.

Instead, Posner recommends measuring how customers’ spending behavior changes in response to incentives. This would include the “incremental revenue growth of existing members – the extra purchase in the basket, the extra visit to purchase influenced by the program mechanics”.

So, in the rest of this article, we’ll talk about the most important focus-areas for loyalty investment, and propose ways to demonstrate predicated ROI on these changes.

Much of this evidence probably already exists within your company. In the past, there will have been cases where customers have shown greater loyalty before or after a redemption. If your points have been devalued in the past, there will have been cases where members have quit your program because they no longer saw the value.

But this data may not all be in one place, and some of it could be out of date. A 2024 study published in Harvard Business Review, ‘Why Loyalty Programs Fail’, gave the example of one brand which had miscategorized customers as low-value simply because they were looking at the wrong data.

“When one of the largest retailers in Asia analyzed its customer base, it found that many consumers originally classified as low value (by average monthly spending and number of trips) were in fact high value (based on gross margin per item), and thus deserved more benefits than they received.”

So really, this kind of evidence-building requires a focused, ongoing effort, so that you can be sure of having the data at hand to support your initiatives.

It’s worth mentioning that optimizing loyalty ROI is like optimizing many other areas in the business. Common focus areas for business optimization include supply chain and inventory turns, or balancing the build-versus-buy decisions in product development, and cashflow management, i.e., to reduce the need for equity to support growth.

These areas of optimization are so well established that budget-holders across the business know that certain types of change are harmful or productive. They know, for instance, that holding a lot of static inventory in the warehouse is expensive – but they may not appreciate that acquiring a lot of inactive members in the loyalty program can be similarly wasteful.

As an industry, we need to strive towards reaching that same level of consensus in loyalty marketing, to resolve persistent areas of misalignment around best-practice loyalty strategy.

So, these next three sections offers some suggestions on how you can accumulate the evidence senior stakeholders may need to invest adequately in loyalty marketing.

Get the C-suite excited about infrequent customers

Historically, loyalty investment has flowed disproportionately towards rewarding frequent, high-spending customers.

Certainly, rewarding good customers is important. And on a per-member basis, high-spending members carry out the greatest number of transactions, which makes them look like sensible targets for incentives.

But brands should really be trying to establish how much value to offer these highly-frequent customers – because you could argue they may have made the purchases anyway.

Industry professionals should also be working to figure out which less-frequent customers would become more frequent, if the rewards were more attainable.

These less-frequent customers are the biggest growth opportunity in most loyalty programs. The distribution of customers of a typical brand will look like this: a smaller number of frequent customers, and a vast majority of mid-to-long tail customers who spend less often.

Most of these mid-to-long tail customers are occasionally spending with competitors – some of them, heavily. You just have no idea who they are, because you may not have provided the right incentives (yet) to capture the majority of their spend in your category.

So, that’s the rational argument. But showing this graph to your CEO won’t be enough to sway opinion when it comes to budget negotiations.

What you probably need to do is show that incentivizing these less-frequent customers turns up a few with much higher spending power, who you didn’t previously know about.

How to prove this in your business

A good way to prove this would be to analyze how a given accrual transaction affects the behavior of customers of different profiles.

For example, you could give an attention-grabbing incentive (i.e., $10 in points value) to a sample of 100 customers, and ensure the sample has a good mix of:

- new members who receive the points as an incentive to join the program

- longstanding members who are already frequent

- longstanding members who were infrequent – perhaps shopping only once or twice per year.

In all probability you would find the customers’ behavior changes as follows:

- some of the new members become frequent – but you may incur some waste as a portion of people join for the bonus but then lose interest

- the customers who were already frequent change their behavior the least

- the longstanding, infrequent members are the most likely to increase frequency with the brand.

Over time, you should build up enough evidence to say that ‘X’ amount of change in loyalty incentive equates to ‘Y’ percentage improvement in customer expenditure with the brand. That, in turn, can allow you build a case that the greatest incentives should be applied to those members where you are capturing less than 60% share-of-wallet.

Of course, there is also a human component to this, in alliance-building and internal stakeholder engagement.

The battle for investment faced by the loyalty team is often similar to that faced by their colleagues in customer experience (CX). In a 2021 interview with various brand CX leaders, former Stagecoach customer services director Keith Gait commented…

“At one company I worked with, we were able to show that every 1% of churn affected revenue by £10milllion, and that churn was directly caused by [low] customer satisfaction”

…but multiple other experts interviewed added that a degree of storytelling was required to make this data seem important to the relevant senior stakeholders. Centrica CX lead Patricia Sanchez Diaz said, “Storytelling + CX analytics that will be the formula to generate funding”, and Gartner analyst Augie Ray said…

“CX leaders must answer the ROI question in a way that doesn’t merely turn CX into another strategy for lowering costs or lifting acquisition. Instead, leaders need an approach that demonstrates how the company profits when customer expectations are understood, their needs are met, and their relationships strengthened.”

If a company says they are customer-centric, but then the loyalty marketing initiatives are not embedded across the company, then such speak is just hollow. Simply look at the brands with the greatest followings of loyal customers; they walk the talk, and all (or at least most) customer touchpoints are engineered to create value for all stakeholders, and promote brand affinity.

It’s your job to accelerate points transactions, in order to build richer customer profiles

Richer customer profiles in themselves don’t generate improved ROI, but they can dramatically improve targeting and personalization, which in turn improves conversion.

Better conversion directly improves ROI.

Often, the loyalty program is the key to getting customers to opt into zero-party data collection within your own four walls, and across a network of partner brands where they also shop, revealing insights that you’d never collect on your own.

This accelerated earning yields more data to tell you which customers you can incentivize with the likelihood of greater ROI. This data also unlocks further efficiency gains, powering personalization efforts across the wider business.

The C-suite shouldn’t need convincing that this data is important; practically all brand executives are sold on the importance of personalized marketing. They might, however, need help visualizing a return on the direct cost of these accelerated loyalty transactions.

This issue has been topical recently, as airlines have struggled to make reward inventory available at a time of peak demand, devaluing their currencies in an attempt to balance demand and supply.

Ten years ago, the CEO and CFO of the largest loyalty programs would target 25-30% ‘breakage’ (where points expire) each year. The CFO may adjust the value of points/miles; the revenue management team may limit the available inventory for redemptions – ultimately it’s the same effect of making the points harder to use.

It is much better to build loyalty and capture share-of-wallet by serving members well, and ensuring they achieve valuable outcomes by behaving in a truly loyal manner.

As a general rule, 5-10% of points should expire every year because people die, move, lose interest, or simply aren’t that desirable as customers.

But the best performing loyalty programs have discovered any level of breakage above 10% to 12% depresses ROI, because too many customers are frustrated in getting to interesting rewards – so they disengage altogether. Points incentives work, fundamentally, because the points are valuable and useful to the customer. So when a customer suffers a loss of value – because the brand devalues the points, or because the points expire – the loyalty team loses its most powerful tool for influencing customer behavior.

The goal should be to deliver sufficient value to customers that most of them are earning points frequently (directly with you or through partners), and that they reach at least $25 worth of value per year. If they can reach this level of value, the customer will continue engaging, and you’ll continue to gather the data needed to motivate further spending and inform further personalized marketing.

If your members can’t get to about $25 per year in points value, then you need an additional value proposition (like recognition or unique experiences), or you need more partners. This is why CXO buy-in is so important. The entire company needs to be working toward creating loyalty – not just propping up that perception with points.

An industry-wide trend in accelerating points transactions

To build this case, a good place to start would be to point at a growing number of examples of brands working to drive loyalty transactions, even at the expense of other priorities.

A loyalty partnership between Bank of America and Starbucks allows customers to bypass Starbucks’ own loyalty app. Now, Bank of America card-holders have the option to earn their Starbucks rewards via card-linking when they pay with their bank card.

The calculation here is that this transaction data is so important, Starbucks is happy to collect at least some data for customers who fail to open the app, for whatever reason, rather than collect no data at all.

Similarly, Retail Brew, an industry journal, recently wrote of three enterprise brands incentivizing non-transactional forms of engagement. Rip Curl, KFC, and Bergzeit offer points, or free food, when a customer engages with their branded digital experiences on their devices.

All these initiatives are coming at a direct cost – but in each case, the brand has calculated that this is a worthwhile cost of data-gathering and improved brand engagement.

And in some cases, points transactions themselves can be highly lucrative. In fact, it’s entirely possible that your best customer may never spend cash – i.e., if they’re earning their points on co-branded credit cards or from other issuing partners. Illustratively: if an Avios member earns 50,000 Avios by spending on the AMEX credit card or with other partners, IAG could have earned roughly £500 by selling Avios which may then be redeemed for distressed inventory with a direct cost of only £25 – a whopping £475 contribution margin.

Or, worse but still very attractive: if that flight had a cash price of £350, the £500 from selling points to partners is more lucrative than selling the seat directly to the customer for cash. Despite a growing body of such evidence across the industry, however, the importance of loyalty incentives for driving data collection is not resonating with the senior leadership team at every brand. So you should also look for evidence within your own business and find ways to make results more visible.

How to prove this to the C-suite

It should be relatively easy to demonstrate that when members can earn greater points value, they frequent the brand more often. But the most influential data will show this in terms of ROI on the individual customer.

Of course, the ultimate ROI metric is Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) – but this can be difficult to calculate. You should, however, be able to test the impact of slower or faster earning across a sample of customers.

The optimal pace of earning is a question of balance. Front-loading accrual with large sign-up bonuses might be exciting, but it may also attract mercenary customers who quicky forget about your brand once the initial benefits come to an end.

But if you stagger out the earning, the customer not only earns a worthwhile amount of points, but receives regular emotional boosts which builds brand affinity: the start of a loyal relationship. Brands often engineer this by setting ‘challenges’ that customers must achieve, or milestones they must pass, to obtain greater value.

You will need to look at different customer segments, who earn their points in different ways, to determine what path of actions keep them engaged without breaking the bank.

In the grocery or retail sectors, this earning would nearly always come from spending cash with your brand, so showing ROI on this engagement should be easy. In the travel sector, much of the earning will be via accrual partners, so you would need to factor margins on the sale of points to those partner into your transactions.

And of course, you should also look at what happens when the customer’s earning trajectory goes backwards, i.e., their points expire, or were subject to devaluation.

If your loyalty currency underwent a devaluation more than 12 months ago, you may actually have some of the most useful evidence you could hope for.

Following such an event, you should easily be able to look at a sample of 100 customers who were members 12 months before the devaluation. From one period to the next, you will almost certainly see that cash spending, points transactions and partner accrual fell on average across the sample.

If you haven’t undergone a devaluation event recently, you could expect to find similar changes in behavior among customers whose points expired – which might help you forecast the impact of a proposed devaluation.

For truly useful tests, you should select your samples to be representative of the whole membership – with roughly the right balance of frequent and infrequent customers, of different income levels, etc.

This will allow you to scale your findings across the whole loyalty program, to show the potential ROI on accelerated earning, and the risks associated with slowing down customers en route to interesting rewards.

More, smaller partners make for a healthier program

Collecting points has long been associated with luxury lifestyles. Certainly, the possibility of luxurious or other aspirational experiences, such as free fights or discounted hotel stays, is a powerful emotional motivator for most customers.

Brand executives can often be swayed by the emotional pull of prestigious brand partnerships that are fun and impressive to talk about. However, a few flagship partnerships may only appeal to a subset of your loyalty program members.

It is much easier to generate impressive KPIs across a larger numbers of smaller accrual and redemption partners, in more spending categories.

The demand-and-supply crunch in enterprise loyalty programs

Many enterprise loyalty programs are competing for similar customers: wealthier individuals who spent a lot with the brand directly – and middle-income customers, who earn the points using co-branded credit cards.

Brands have become quite good at acquiring these customers, including with new member bonuses. If the customer spends heavily on a branded credit card in the first 3-12 months of their membership, this can accelerate the path to a desirable reward – say, a hotel room or flight worth $1,000 face-value.

This is effective for new customer acquisition. But after that initial redemption, the ‘earn rate’ on such a credit card typically drops to about $200 in points value a year, assuming the customer allocates $10-20,000 worth of spending per year to that credit card.

A $200 redemption might sound attractive, but for $10,000 in spending, customers know they can do better – often by switching to another co-branded program.

This is accelerating a longstanding problem where customers are members of steadily more programs, but are progressively less active in each one. A 2024 report by the Boston Consulting Group put the average figure at 15 loyalty programs per customer – up 10% on 2022 – and added…

“Consumers are 5% to 10% more inclined to consider switching to another loyalty program within the same industry or product category compared to two years ago. More than 35% of respondents told us they planned to cancel some of their memberships in the next year…”

This is leading to a second problem, which is that there is too little reward inventory in many loyalty programs for the large numbers of consumers who are able to accelerate their earning with co-branded credit cards.

Anthony Woodman, VP of Virgin Atlantic’s Flying Club, rightly cautions that an eventual flight redemption needs to be on the cards to keep members engaged. And airlines may struggle to see the point in making reward seats available when they’re easily selling most of them for cash.

But this is short-sighted, because major loyalty programs are wasting a lot on points issuance, for customers only then to quit the program, creating a bad memory of the brand. And if members quit, it fundamentally undermines the value of the loyalty currency which remains one of a brand’s most cost-effective tools for influencing customer behavior.

How brands are solving this problem

One obvious answer to this challenge is to add further reward inventory but there needs to be a balanced approach to this. As mentioned, the brand may be able to generate more revenue selling points to accrual partners, than the cash price that the customer would have paid for that inventory. But some customers will only ever spend cash – so there will always be some limit to proprietary reward inventory.

The other answer is to add more loyalty partnerships so that every customer can earn more easily across a broader ecosystem of partners, or find a redemption of emotional value.

This is now happening across most industries.

In July 2024, Emirates’ Dr. Nejib Ben-Khedher explained on Skift how the Skywards team was focused on helping customers, including infrequent customers get to rewards faster. This includes having accrual partners in many different categories.

Accrual partners will help you collect the most useful data, especially for identifying customers who have the potential to spend a lot more with your brand.

Accrual partners can also correct any misleading signals in your own data. For example, I may fly to London on Ryanair but stay in a 4-star hotel. Both brands could figure out if I was their type of customer, if they know which types of restaurants I frequent or the quality of shoes I wear.

But redemption partners are also extremely important. Hilton allowed their members to spend their points directly on Amazon a few years ago. The value compared to redeeming for hotel rooms is questionable, yet the level of member engagement skyrocketed because the points, even with a low balance, became immediately useful to every customer.

How to prove the value of varied partnerships

To prove the theory here, you will need some existing ‘earn’ and/or ‘burn’ partnerships in your loyalty program.

To measure the impact, you should identify some positive and negative experiences that might have occurred in the lifecycle of a loyalty program member, i.e.:

- an aspirational redemption on your proprietary inventory

- a sizeable redemption on partner inventory

- an exchange of your points into a partner’s currency

- an exchange into your currency from a partner’s program

- breakage – where the customer’ points expire,

Then, you should select a sample of 100 customers who have had these experiences, and analyse the 12 months before and after the event to see how their behavior changed.

For some customers the conclusions will be kind of obvious. Those who are already frequent probably earned most of the points for their aspirational redemption directly with your brand, and continued to do so afterwards.

The really useful data will be on those mid-tail customers whose lifestyles and spending habits are a lot more varied – so you might want to skew the samples to focus on these people.

Next, you would quantify how many different partners they earned or burned with, en route to these events.

And finally, you would want to calculate the profit and loss (P&L) on individual customers’ activity across the whole 24-month period. This could be difficult to do precisely, but if you know the cost/profit on points issuance and exchanges, and your average margins on cash transactions, you should be able to estimate representative data simply from the transaction totals.

The results probably won’t surprise you very much as a loyalty practitioner.

Almost certainly, you’ll see that when customers are rewarded for their engagement in the program, they become more profitable to the brand. And you’ll also see that the availability of partner inventory is critical for stimulating these higher levels of engagement.

But when you scale these findings across the business you should have compelling data that show the C-suite how the makeup of your partner network impacts on CLV.

That, in turn, should enable a much larger and more important conversation about ensuring you have the right tools for job.

Loyalty ROI: a circle of data and modern technology

The experiments we’ve proposed in this article are intended to be manageable for loyalty teams that struggle to report on ROI, yet are motivated to drive change by obtaining greater CXO buy-in.

Really, though, the capture of this data, and consistent reporting on it, ought to be systematized within your business. This will become possible as you adopt more modern technology and reduce the operational complexity that still exists in many loyalty programs.

Based on our estimates, about 60% of the loyalty budget is spent on indirect running costs at a typical loyalty program (personnel across many departments, technology, etc.). With modern, low-cost technology, this could fall to about 25%, unlocking a great deal of budget that could be directed into rewards that influence customer behavior.

Of course, replacing those systems requires some upfront investment. But if you can convince your budget-holders of the growth potential in the program, it refocuses the conversation: from an expensive transformation project, to an investment in growth.

Crucially, brands need to look at accelerating new partner onboarding. Now that customers are actively shopping around for better value, the number of members you keep engaged will be significantly determined by how fast you can optimize your partner mix. That means having ‘earn’ and ‘burn’ options that appeal to nearly every customer and keep them engaged with your brand – even if they don’t have a need to buy often from you.

Let’s assume that the average new loyalty partnership adds 0.25% incremental revenue to your loyalty program. If your business has the capacity to onboard 10 new partners per year, that means the value of your partner networking efforts is capped at +2.5% annual recurring revenue (ARR). If you can onboard 20-30 new partners per year, the incremental revenue starts to look a lot more interesting.

More importantly, those extra partners capture the attention and imagination of your broadest membership base – so they are motivated to engage with the network on a regular basis.

As loyalty teams’ systems and reporting capabilities mature, the upside potential of the loyalty program, and the factors that unlock this, should become commonly understood by most stakeholders. Eventually, this should alleviate some of the contention over budgets and get to the point where the C-suite more readily backs loyalty investment.

But budgets are always going to be competitive and subject to negotiation – and you can’t wait for a wholesale loyalty transformation to take place to build your case.

You already have much of the data in your business that is needed to show the impact of that change. But collating that data and making it digestible for the wider business requires some immediate focus, if you want to achieve amazing things in 2025 and the years to come. So if you’re not already on that path, the time to start is now.

Please contact Currency Alliance if you would like to discuss this topic in greater detail, learn about interesting use cases, or evaluate how adding partners can dramatically improve the value proposition for both internal stakeholders and your members.