The Experience Margin: Only CX can save retail brands

Retail brands can be saved; but not by conventional retail strategy.

In an economy where it’s no longer possible to profit off physical goods, the most successful businesses today are migrating their profit centers on to services and experiences.

While some retailers are making progress on this front, most continue struggling to face this reality.

Their increasing woes are a consequence of their fixation on product margins.

This has come at the cost of innovation, experimentation, and ultimately customer experience.

Agile technology businesses, meanwhile, take advantage with gusto of the retail establishment’s sluggishness in embracing change.

With so far to fall, it’s high time retail giants stopped dragging their feet.

Shrinking retail sector

The old-school retail business model – buying product at wholesale and selling it on for a profit – is in long-term decline.

Despite a successful 2017 holiday season[i], commentators talk of a “retail apocalypse” and stories of store closures abound[ii].

As I discussed last month, this is because margins on goods have reached a point of saturation, leaving no more room for growth.

This has reduced “success”, in today’s retail industry, to the risky task of keeping up with inflation, rather than getting ahead of it.

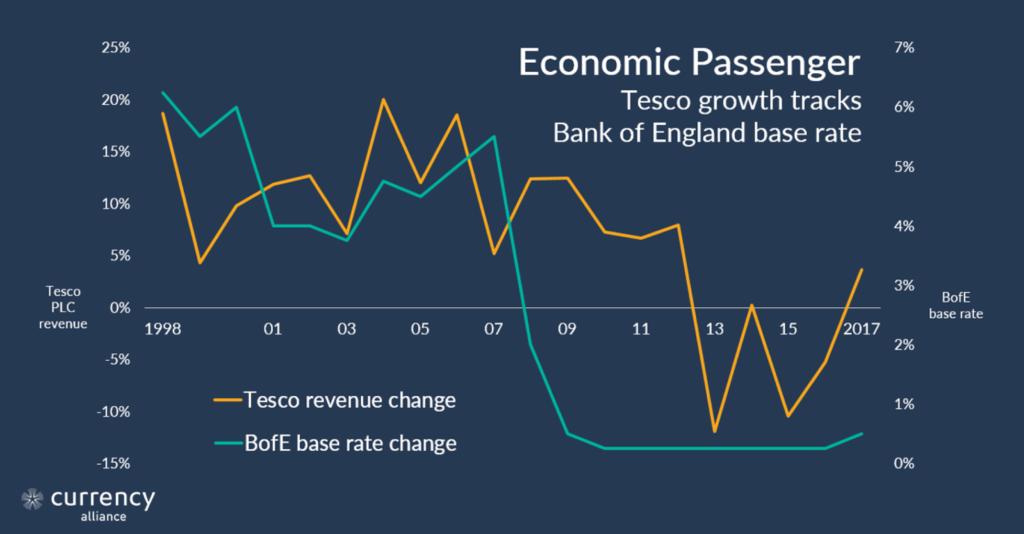

You can observe this in the last 20 years of Tesco’s growth, which obediently correlates to the Bank of England base rate.

This is tantamount to shrinkage – because as the economy expands to accommodate new services and innovative customer experiences, retail occupies an ever smaller market share.

This is tantamount to shrinkage – because as the economy expands to accommodate new services and innovative customer experiences, retail occupies an ever smaller market share.

Businesses at the zeitgeist of the experience economy, on the other hand, grow regardless.

Most commonly cited are Uber and Airbnb – neither of which provide a traditional service, but both of which sell the experience of one.

But for more relevant inspiration, retailers should turn instead to larger, older organizations making concerted efforts to remodel their businesses around experiences.

The best example is Amazon.

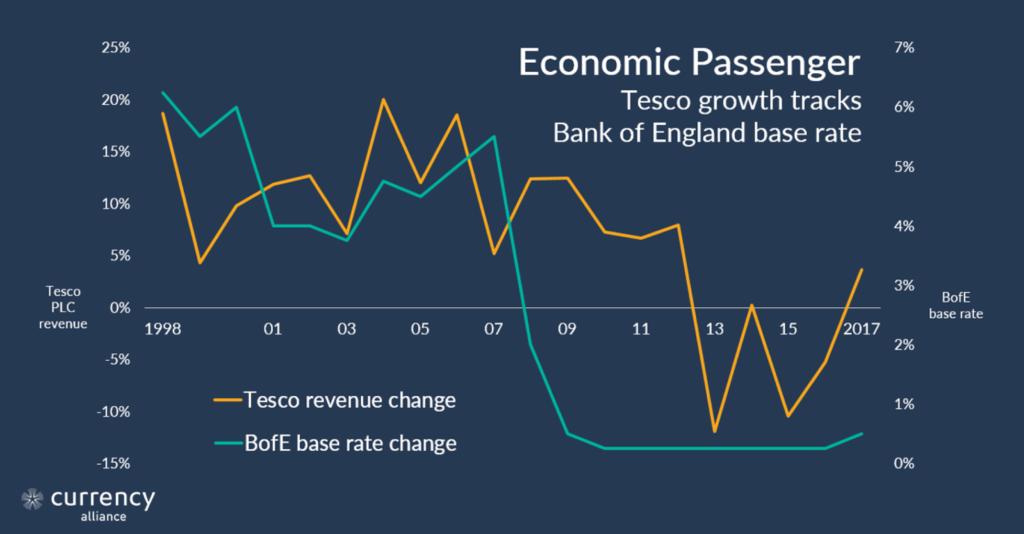

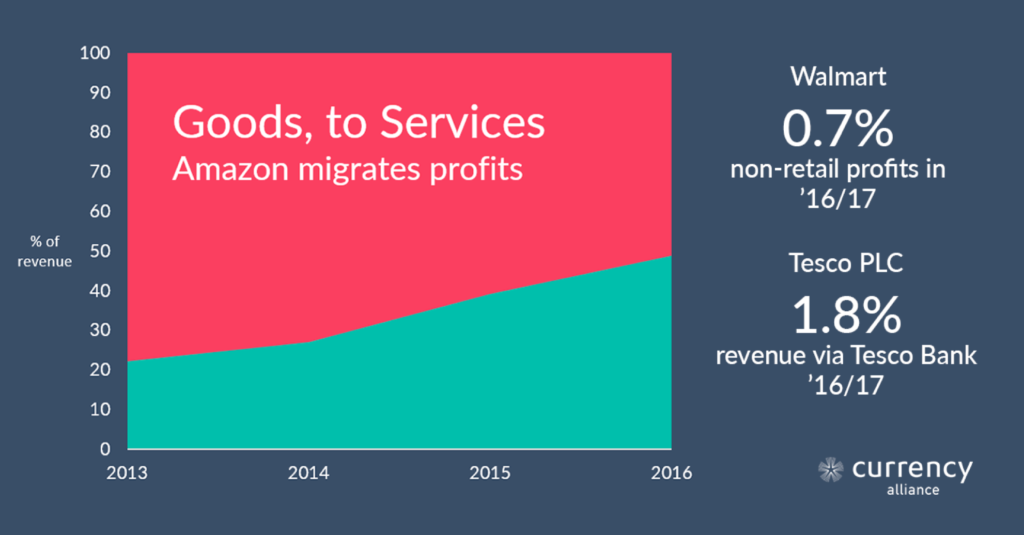

The online giant is aggressively migrating its business away from a dependency on product margins.

Illustratively: in 2013, Amazon’s services (Prime, third-party sales, credit, advertising and AWS) formed 22% of Amazon’s group revenue[iii].

By the end of the last financial year, this had risen to almost 50%[iv].

Similarly, IBM is “in the throes of a revolutionary five-year strategy to shift its product focus to software and services”[v].

Similarly, IBM is “in the throes of a revolutionary five-year strategy to shift its product focus to software and services”[v].

Such businesses are being rewarded with new leases on life, for having successfully responded to a seismic economic shift.

This is less a case of clever manoeuvring; more, of stitches in time.

The warning signs have long been plain to see.

Money for something

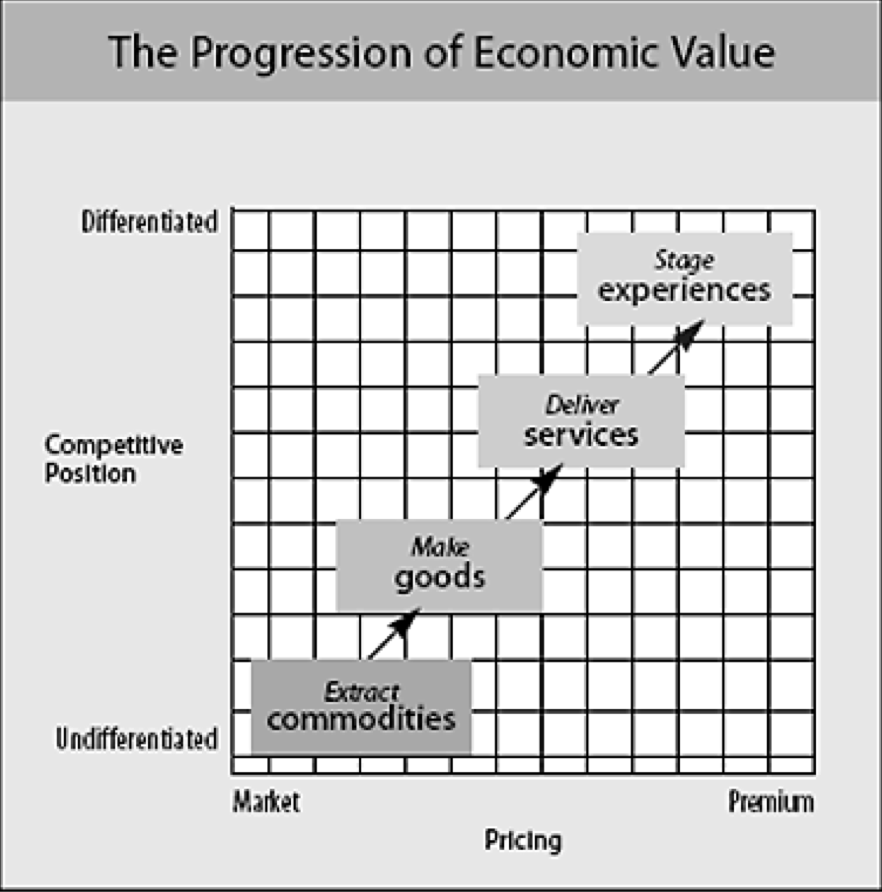

In its 1998 paper, “Welcome to the Experience Economy”, Harvard Business Review posited that a shift, from a goods-based economy to an experience economy, was a natural “progression of economic value”[vi].

It gave the example of an Israeli café opened that sold nothing; clientele paid $3 at lunch and $6 at dinnertime to be brought empty crockery.

“People come to cafés” explained the manager, “to be seen and to meet people, not for the food.”

The café soon ceased trading, and rumours have since surfaced that it was only ever intended as an art project.

But as is often the way with art, the stunt proved to have been an astute piece of satire on real, burgeoning change.

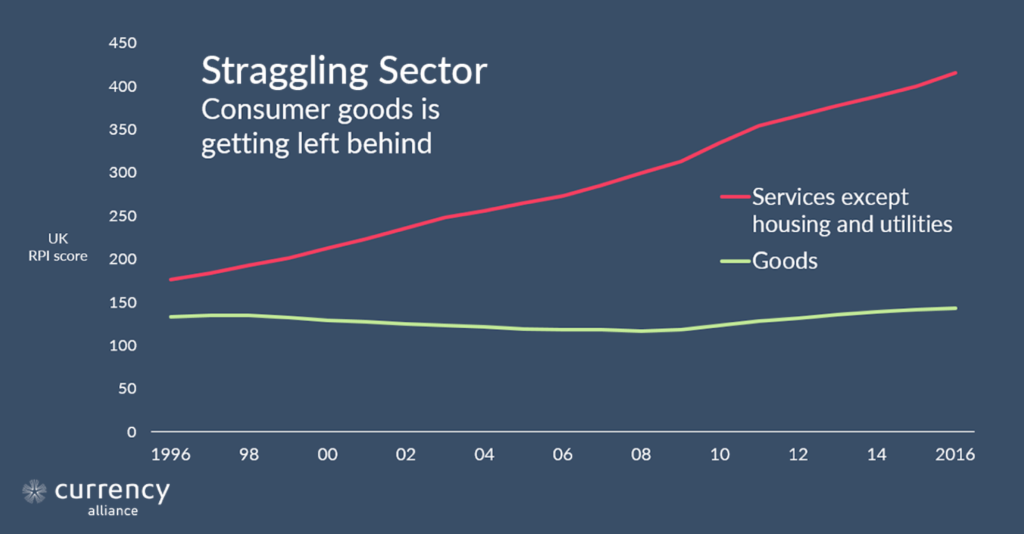

Twenty years on from the Harvard Business Review’s paper, economic data do indeed show that as relative economic sectors, goods has remained stagnant, while services is on the march.

The UK’s RPI data shows services becoming progressively more valuable over time, whilst consumer goods remains flat[vii].

The American economy mirrors this trend[viii].

The American economy mirrors this trend[viii].

Herein lies the answer to the retail industry’s woes.

Most retail CFOs would spit coffee at the suggestion that customer experience is their problem, but services can be easily and practically budgeted for, commoditized and recorded in a brand’s annual reports.

This has repeatedly been proven by other firms in other sectors.

A 2015 PwC report sounded the death-knell for no-fees banking in the UK.[ix]

Santander’s increasingly expensive 123 current account is one popular example of a working solution[x], retaining customers on a monthly fee in exchange for a wide range of benefits.

This is, in effect, a monetized loyalty strategy.

It’s the same logic by which American Express cards work. You can pay hundreds of dollars a year for an enhanced experience of spending: not only in collecting rewards, but also a sense of camaraderie in knowing your card issuer will always back you up in case of disputes with merchants.

This tactic is also extant in retail.

Amazon monetizes experience through Amazon Prime – covering the cost of a game-changing one-day delivery service through a monthly or annual fee.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Target earned the right to charge a premium over Walmart by investing in making its stores nicer places to shop.

And Costco has been charging memberships for decades, proving that shopping itself can be monetized; not just goods.

Missed opportunities

Like the anomalous wins of a bedraggled sports team, incidents of the retail industry dabbling in services are almost more frustrating for their paucity.

Granted, the appearance of pharmacies and bank branches in supermarkets have resonated with consumers, and certainly home delivery and installation services have added the appeal of convenience for busy shoppers.

One more exciting recent example was UK supermarket chain Waitrose’s decision to pilot evening yoga classes in its stores[xi].

But at 7 a pop, these classes are likely to be a sticking plaster over industry-wide lack of zeal when it comes to embracing new business models.

But at 7 a pop, these classes are likely to be a sticking plaster over industry-wide lack of zeal when it comes to embracing new business models.

Tesco PLC has made the most serious efforts.

The 1997 launch of Tesco Bank was the group’s first major step towards diversifying profits away from margins on goods.

Today, however, the bank’s 1bn annual revenue still only accounts for less than 2% of the group’s total.

Tesco Mobile does not feature separately on their annual report, but seems unlikely[xii] to haul in more than 1b in annual sales[xiii].

Tesco Home Phone & Broadband was sold in 2015[xiv].

In truth, the track record of supermarkets in the services sector has often been one of fleetingness and retraction, rather than boldness and endeavour.

Tesco had once been considered a market leader in launching its loyalty program.

This year, news of its decision to curtail the program (well-synchronised with news of Sainsbury’s acquisition of Nectar[xv]) riled customers[xvi], proving that they highly valued this enhanced experience.

Tesco duly forestalled the changes, but it was a telling irony that this news broke in the same week that Amazon announced an increase in the cost of Prime membership.

And Amazon had no place becoming the world’s leading online retailer, when you consider that the first ever online order was placed with Tesco via Teletext in 1984[xvii].

“Tesco Prime Video” was there for the taking.

Of course, there are other ways that supermarkets and retail businesses can boost physical sales too.

For example, studies consistently show that the use of self-service checkouts is on the rise. In the uk kiosks are hugely popular.

It is thought that self-service kiosks are a far more enjoyable alternative for customers in a rush as it is comparatively quicker to use a self-service kiosk as opposed to dealing with a store assistant.

Ultimately, it will be interesting to see how the retail sector continues to adapt and embrace self-service technology in new and exciting ways.

Bridging the gap

To synchronise their businesses with the changing economy, retailers must cease to view sale of physical goods as a raison d’être, and start viewing them as a passport to other, more profitable forms of trade.

The simplest way to achieve this is by migrating into services – a strategy which has been repeatedly proven across diverse sectors.

Spotify offers one delightfully quirky example of how simple this can be.

When the music streaming service heard that dogs have their own musical tastes, they swiftly forged an alliance with a Munich dog shelter[xviii].

So while the songs available through Spotify remain the same product – also available via numerous other suppliers – “Adoptify” is now a new, valuable customer experience: a clear market differentiator with unique value.

Spotify gained an extra $3bn in valuation this year[xix], a leap of 23%, and its ability to woo investors grows.

Spotify gained an extra $3bn in valuation this year[xix], a leap of 23%, and its ability to woo investors grows.

Granted, major retail groups will never be as agile as tech startups.

I would not envy the task of telling the board of any major supermarket chain that their only hope of salvation lay in annexing dog day-care onto all their major stores.

But the fact remains that retailers’ bread and butter – consumer goods – are low on profit, and light on experience.

When you buy a popular consumer product, the experience you remember (if you remember it at all) is likely to be almost indistinguishable from that of buying the same product elsewhere.

Services are more variable.

Whether it’s yoga at Waitrose, cheap content streaming via Amazon, or soundtracks for your dog via Spotify, it’s in this growing economic niche that true differentiation occurs.

It’s in experiences, deriving from services, that retailers will find their best hope of continuing to nurture customer loyalty and repeat purchasing.

Ultimately, that’s where the real profits lie.

Could your retail business offer a better customer experience?

Currency Alliance can help.

We help consumer-facing brands revolutionise their loyalty programs, maximising participation by customers, and earning of data by businesses.

Our free, simple, cost-cutting SaaS tech platform is used by Loyalty Managers to issue, buy, sell or exchange loyalty currencies with other brands.

This helps brands turn dormant points into profit, whilst customers earn and spend their points freely, and enjoy more relevant rewards.

To discover the full range of benefits, explore the platform and get in touch at CurrencyAlliance.com.

References

[i] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/12/business/holiday-retail-sales.html

[ii] http://uk.businessinsider.com/store-closures-in-2018-will-eclipse-2017-2018-1

[iii] http://uk.businessinsider.com/how-amazon-makes-money-2017-12?r=US&IR=T

[iv] http://uk.businessinsider.com/how-amazon-makes-money-2017-12?r=US&IR=T

[v] https://www.forbes.com/sites/ciocentral/2012/04/19/services-not-manufacturing-will-revive-the-u-s-workforce/#754444612464

[vi] https://hbr.org/1998/07/welcome-to-the-experience-economy

[vii] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/consumerpriceinflation

[viii] https://www.forbes.com/sites/ciocentral/2012/04/19/services-not-manufacturing-will-revive-the-u-s-workforce/#754444612464

[ix] http://pwc.blogs.com/press_room/2015/02/pwc-current-account-fees-are-the-future.html

[x] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/11/08/santander-123-account-holders-will-miss-interest-rate-rise/

[xi] https://www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/2018/02/waitrose-ends-confusing-loyalty-scheme-rolling-yoga-classes/

[xii] https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/060215/what-average-profit-margin-company-telecommunications-sector.asp

[xiii] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/may/08/tesco-mobile-sale-debt-o2

[xiv] https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/news/utilities/2015/01/talktalk-to-take-over-tesco-broadband-and-home-phone-customers

[xv] https://www.ft.com/content/584f106e-0766-11e8-9650-9c0ad2d7c5b5

[xvi] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-42700758

[xvii] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-24091393

[xviii] http://www.adweek.com/creativity/spotify-gets-into-pet-adoption-after-learning-dogs-have-their-own-musical-tastes/

[xix] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/10/12/report-on-spotify-earnings-h1-2017-revenue-loss-margins-growth.html